Down the River

There is no time on a river. There is only light and dark. The river becomes your clock, your controller. The river decides where you go and when you get there. One can either accept this—embrace it, give oneself up to it entirely—or not; the river is indifferent.

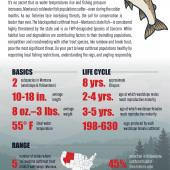

For about a third of its 92 miles, the Middle Fork of the Flathead tumbles through the Bob Marshall Wilderness, a land untouched, unhindered, and unblemished by the hand of man. This is why the imperiled Westslope cutthroat trout still thrives here: because Homo sapiens ignoramus doesn’t. The water is so clear I can count pebbles on the bottom of deep pools. We float through a land of rolling green mountains, trees, and rock. It’s a country as vast and awe-inspiring as I have ever known. It’s easy to find places in Montana where you feel alone. In “the Bob,” you really are.

Night-fishing for catfish in Vermont, poaching bass on a Massachusetts reservoir—this is how I grew up fishing. Until moving to Montana, I knew only what Norman Maclean told me about fly fishing. The first time I showed up at a local river, my spin rod received the same look I might give a strange rash sprouting in my nether regions. Habits learned in childhood are hard to break, though, and I stubbornly wielded that spin rod, scornful looks from fellow fishermen bedamned.

But any real fisherman knows that to catch fish one must be willing to adapt. So when I was offered a trip to the Mecca, the Holy Land, the very Church of Trout—and informed that my spin rod would not be welcome—I knew I was at a crossroads. This is how I came to find myself, moderately hung over, staring at the smelly end of a mule being loaded with all my gear, about to begin a four-day fishing adventure down the Middle Fork of the Flathead River.

As our guides from Glacier Raft Company—Darwin, Mark, and Ryan—loaded the boats, Hilary Hutcheson, host of the popular show Trout TV, took me and another rookie fly fisher to a long aquamarine pool for a casting lesson. Hilary was like General Patton with her barrage of instructions: don’t bend your wrist, don’t make a rainbow more of a straight line, up-wait-cast, up-wait-cast, mend upstream, mend downstream, let it drift, you bent your wrist. I yearned for my spin rod. A small riffle rolled over a submerged ledge just at the head of the pool—a perfect spot, but it was over 50 feet away. On a good cast I could maybe get the neatly arranged piece of belly button lint I was trying to hurl with a half-cooked piece of spaghetti half that distance. I felt ridiculous. Might as well be throwing a balloon into a headwind.

After five minutes with a fly rod I was dangerously close to breaking the damn thing and tossing it into the woods. I chose the high road and leaned it against a tree, then sat down on the rocks to compose myself. Dan, one of the guests who could actually fly fish, eased into the spot I’d just vacated. He made a couple false casts to let his line out, not letting the fly touch the water. I had to admit, watching him do it properly, effortlessly, I could almost see the power, the energy flowing up his arm, into the rod extended skyward, into the line that danced hypnotically above his head… it was a beautiful motion. I imagine that’s what the breeze would look like, if we could see it.

Dan let the line go; like a dart the fly zipped over the pool and landed in the ripples above. It floated, a white speck on blue water, down toward the edge of the pool. “There!” Hilary yelled, as a trout snatched the fly. It was a beautiful 12-inch cutthroat. Its colors danced in the sunlight. It looked like something from a rich guy’s aquarium. And this was my first lesson about the trout of the Middle Fork: put a fly in the vicinity of their mouths and they will almost certainly take it.

Down the river. All forward, right back, drift. This is all that’s asked of us for four days. Life becomes a pleasant rhythm of short, fast rapids rolling into long mellow pools of emerald water. We fish almost every pool, and though I can’t cast to save my life—I’m basically slapping the water over and over with a cotton ball—still those lovely cutts keep sacrificing themselves for my enjoyment. One after another, in each pool, they take my clumsily presented flies. 12-inchers, 14-inchers, 16-inchers; you name, we catch it, over and over again. Heather even gets a 20-plus monster on, but it breaks her tippet while being netted. It’s not fishing on the Middle Fork, it’s catching. Heather even mentions how it’s not about the best cast, or the perfect fly that leads to success, but rather about being the first person out of the boat, the first person with a fly on the water. I grudgingly begin pondering if I could ever have such success with my spin rod.

On the last night I marvel at how our guides seem to have created the ideal river experience. Things appear at the very moment you want them, if not before. These guys know the river, the country, and how to create comfort, even luxury, in a remote wilderness setting. Tell me the last time you sat by a fire in the backcountry, washing down your fish taco with a beer chilled in the river, only to be told there was pineapple upside-down cake made in a Dutch oven for dessert. Or slept a completely unbroken sleep, lulled by the soft sound of the river. Or hiked seldom-used trails to clear-water lakes in deep glacial cirques, then up to a ridgeline to watch the sun set on the rugged peaks of Glacier National Park.

When we pull into our takeout at Essex, I almost refuse to get out of the boat. I know that once my feet touch that sandy soil, what can only be described as a four-day orgasm will come to an end. Let’s keep going, I beg, just a little further, please God, please Darwin, just a little further, down the river.