Higher Education

One Montana launches Master Hunter program.

Montanans value public land and private-property rights equally. Now more than ever, a schism between the two has set us at odds. In attempt to mend that tear, Bozeman nonprofit One Montana created the Common Ground program in 2012. This year, Common Ground made considerable strides for the hunting community, celebrating 25 graduates from their Master Hunter program in its innagural session.

Montana Master Hunter is an advanced hunter-education curriculum. It connects hunters to landowners in an attempt to bridge the gap between these two groups. “We just wanted people to come out with a really deep and dynamic understanding of conservation issues and private-land-ownership issues related to wildlife and managing hunting,” says program manager Zach Brown.

Brown explains that Master Hunter is landowner-driven. Most public-access programs have a catch in which landowners are expected to give back or give up something, which often deters them from opening their land to hunters. “It’s fun to be able to say that we want to help meet landowner needs,” Brown says. “We’ve designed a program that’s totally to their specifications, and we have some really thoughtful folks that aren’t necessarily antler-chasers or trophy hunters.”

As Brown described it, limited options exist for landowners and hunters. Type I Block Management is a no-contact deal, meaning hunters sign their name on a pad without engaging in any conversation with the property owner. Since the land becomes overrun by the public, Type I generally results in less game available to hunt. With Type II, there’s a little more sophistication and restriction; for example, ranchers can assign pastures or limit the number of hunters. This type gets less pressure but also requires much more coordination and direct contact between hunter and landowner, which is another deterrent.

Master Hunter creates a third way to manage access: the landowner has more control over the property without stifling the hunter. “From the landowners’ perspective, it’s not just a wide-open gate to anybody,” says Brown. “They are getting wildlife-management help and they have the confidence that the [hunters] respect their property.”

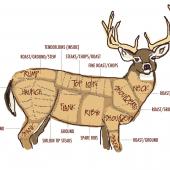

The program allows property owners to create their own access policies. For example, one rancher has a strip of land that connects to a remote location where bull elk frequently gather. In exchange for access, he is asking hunters to donate to the Madison River Foundation, a nonprofit group which sends volunteers to his property each spring to replace temporary riparian fencing.

The program attempts to bring back hunter-landowner interaction. “We have a generation of hunters who, between public land and Type I, have never had to build a relationship with a landowner,” Brown explains. “If you have this culture that’s developed where people don’t even know how to knock on someone’s door and start a decent conversation, then that’s problematic.”

Brown noted the top reason landowners drop-out of Type I Block Management is hunter behavior, and cultivating partnerships between landowners and sportsmen can allow for some accountability should something go awry. “There are real economic consequences for landowners during hunting season,” says Brown. “It’s a tough industry; access and hunting are a privilege and if we don’t nurture it we have the potential to lose it as a management tool and a cultural heritage piece.”

Apart from the typical hunter-education courses most people take at 12 years old, there are few opportunities to further educate hunters. This program offers them the opportunity to expand their expertise and explore ethical questions while learning about conservation and wildlife management. “Our class offers tremendous value, plus the access program at the end,” Brown says. “We’re trying to help train a group of ambassadors who can improve landowner-sportsman relations in Montana and help harvest wildlife, as appropriate, and improve access while we’re at it.”

Learn more at onemontana.org.