Progress or Paradox?

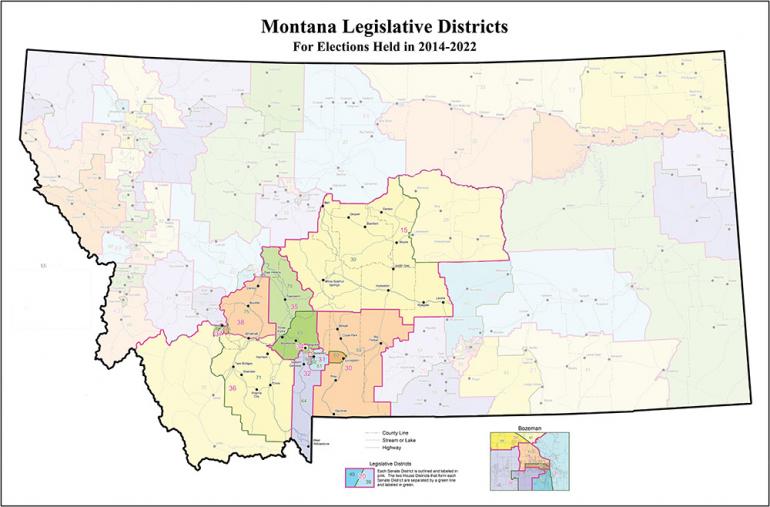

From railroad land grants to modern legislation, politics continue to muddle Montana's values.

Laws affect our lives. Whether their ramifications are felt firsthand, like changes to our immediate rights to land access, or across a larger landscape, such as shifts to the management of our wildlife, legislation has consequences that trickle down to each and every one of us. Who we elect matters, and this is not a call of partisanship—quite the opposite. In fact, this past legislative session shed light on how blindly partisan Montana is. It highlighted that many of us honor wearing our stripes over defending our values. It’s both a scary and strange thought to reach a point where society’s votes are cast in direct opposition to said society’s core values. Is pride the issue? Are we too haughty to bridge the party gap? Have we reverted to sectarianism, mired in blind feuds, demonizing one another without cause? Is it simply a result of not reading the fine print, of not truly understanding a bill’s full implications? Whatever it is, it does not bode well for the future of Montana—a state deeply rooted in public lands, wildlife, and access to both.

Fine Print

A few doozies from 2021

by Chris McCarthy

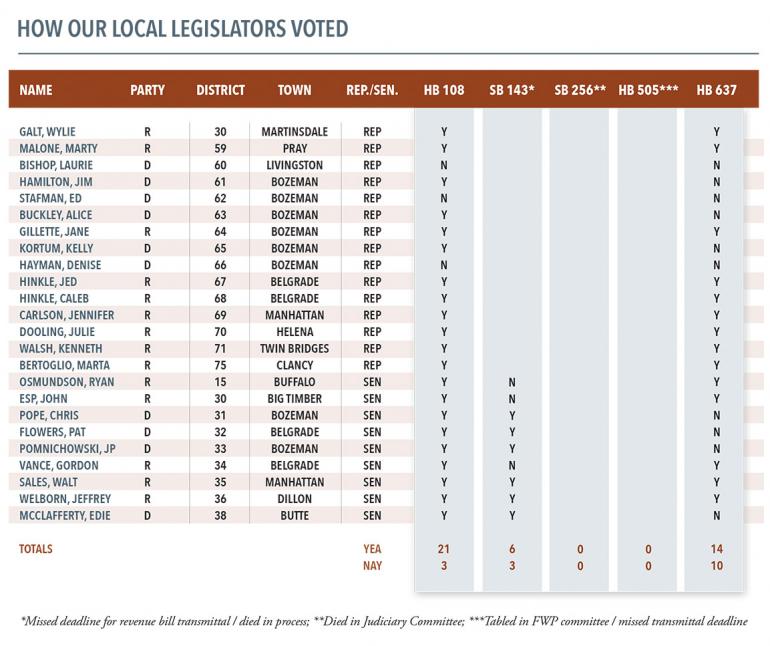

It’s been said that management of our wildlife, habitat, and rivers happens in November at the ballot box. This was never more evident than during the 2021 Montana Legislative Session. A total of 1,313 bills were introduced in less than 90 days. Keeping track of all of them wasn’t easy, but if you paid attention, you noticed that issues related to hunting drew quite the spotlight. Though not all of them passed, here’s a rundown of a few of the more maddening proposals—and, more importantly, how our local legislators voted on them.

Senate Bill 143 – Sen. Ellsworth (R-Hamilton)

Back in 2010, Montana voters approved I-161, an initiative that abolished outfitter-sponsored nonresident hunting licenses, meaning all nonresident hunters would have to go through the same lottery system to get tags in Montana. SB 143 would all but reverse I-161 by guaranteeing up to 60 percent of nonresident combo (deer and elk) licenses go to outfitters and their clients. SB 143 passed through the Senate Fish & Game Committee on party lines, but once it hit the senate floor, was amended to do away with the guaranteed outfitter licenses. The bill passed narrowly on the floor but had to return to the Senate Finance and Claims Committee, where it ultimately died in process.

House Bill 505 – Rep. Galt (R-Martinsdale)

HB 505 would have given any landowner owning more than 640 acres in a unit at elk objective up to 10 transferable, non-resident, either-sex elk tags. As it was written, these tags would have been unassigned—the landowner could’ve sold them to the highest bidder regardless of residency. If passed, this bill would’ve set the stage for Montana to (further) privatize wildlife—not to mention skewing the bonus-point system by rewarding cow-elk hunters on private land with five bonus points toward future drawings. This bill was met with so much resistance that the House Fish, Wildlife & Parks Committee never held a vote. As a side note, Representative Galt’s family owns nearly 250,000 acres of land in Central Montana and would have benefited handsomely from this bill.

House Bill 637 – Rep. Berglee (R-Joliet)

Written as a “catch-all” or “clean-up” bill for all things Fish, Wildlife & Parks, this 32-page bill was a lot to take in. It included changes like bumping the max payout to landowners participating in block management from $15,000 to $25,000, but overall, 637 was a laundry list of items that mostly flew under the radar. One such example being that landowners who own more than 640 acres can now invite non-paying guests to hunt mountain lions without a hound license—this includes on the adjacent public land. Another head-scratching detail delegates $1 million of license dollars to fund pen-raised pheasant transplants instead of habitat improvements. But the real slap in the face came in the form of an amendment, taking substance from SB 143. The addition guarantees nonresident hunters over-the-counter tags, so long as they were unsuccessful in the 2021 lottery but had booked an outfitter ahead of time. Once this final amendment was added, HB 637 was rushed through both chambers in less than 12 hours without public comment or testimony.

Senate Bill 256 – Sen. Flowers (D-Belgrade)

So, as hunters lost their implied right to cross unmarked private property, landowners maintained their ability to deny legal access to public land. Senator Flowers of Belgrade introduced SB 256 to increase the punishment of a person illegally blocking access to public land. The current fine for these unlawful closures is $10 per day. That means a person could illegally block access for just over $300 per month—pretty low rent if the hunting is good. SB 256 would’ve elevated the punishment for blocking access to a form of harassment, coming with stricter penalties and possible jail time. Although supported by many hunting groups, SB 256 died in Judiciary Committee without ever being voted upon.

What all of this adds up to is that last year’s legislative session produced a clear decrease in public-land access and a clear increase in private-land privilege. Is that what we all had in mind when we voted?

The Montana Sportsmen Alliance just released their own scorecard for the last legislative session. Check it out here.