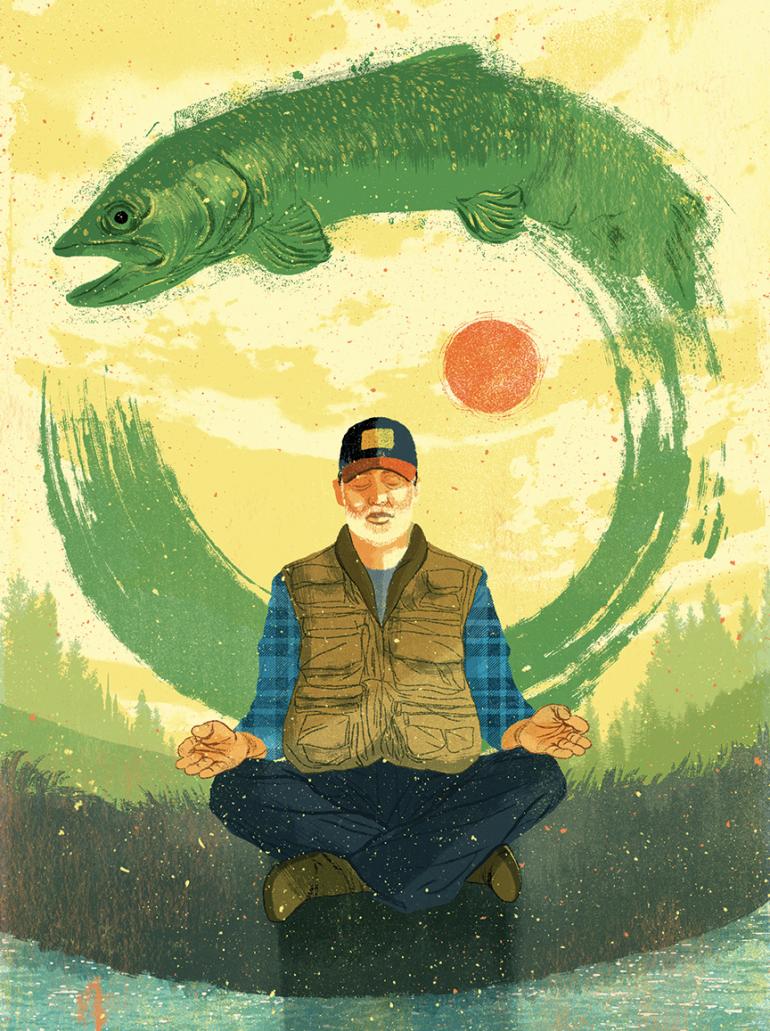

The Curse of the Philosofisher

Rethinking the Zen of fly.

Assuming an overtly contemplative stance on fly fishing is perhaps the cheapest way to make friends in Montana—or enemies, as the case may be. Buzzwords like “peaceful” and “Zen” are the main adjectives at play here, and the sermocinatious fisherman doesn’t neglect to flaunt his five-weight like a baton when making the point. Whipping out one’s tattered copy of Trout Bum or A River Runs Through It in the presence of IPA-sodden compatriots is the regional equivalent of brandishing grandma’s King James bible at a Baptist convention; the faithful are drawn like moths to a flame, or rather, like cutthroat to a #12 stimulator in mid-July. Though I have never bothered to find out myself, if one were to wade through the fly-fishing blogosphere, dozens of posts would crop up entitled, “I Fish, Therefore I am” or “To Catch is Human; to Release, Divine.” But is there any oomph in the offering, any bomb to the bombast, or is the mystic piscator a pseudo-Socratic in angler’s clothing? As a casual caster myself, I have often wondered whether there is anything to the philosofisher’s words; I fear I’ve merely been duped into an elaborate joke.

From Yvon Chouinard to Henry Winkler to the tawny river rat next door, it’s increasingly popular among the outdoor elite to skip the fish bit in the story and head straight into the moral. Boring details that didn’t make it past the cutting room a generation ago are liberally slathered on: “Oh, I throw back anything that couldn’t feed a family”; “Of course, I use a knotless net”; “I can’t imagine bludgeoning a carp senseless.” This is a pretty bad sign for you and I, whose lives are filled with just the right amount of fishing enthusiasm—the outliers have pushed us into the spotlight.

No longer can one affect disinterest; the fishers of men will mercilessly reel you in. Even from the start, the modern fisherman is doomed to face stigma on either side of the spin-cast/fly-rod schism. If he nabs the live bait in the shop, he is a hick or a philistine; if he spends the winter hunched over the vise, he is an aesthete and outdoorsman. The snowbird tycoon and the dirty hippie have demolished the last refuge for the vaguely-outdoorsy-but-definitely-unmacho individual, each searching for that special communion with nature.

But what does the sought-after communion boil down to? Hours and hours in the heat and cold, waving a stick above your head tempting scorn or praise from people who are apparently better at it. All this to maybe, I mean maybe, catch a little forker unfit for the cast-iron. Some call this patience, and others, insanity—after all, what is the fly fisherman doing but the same thing over and over again expecting different results? Being outsmarted by something that billions of people eat every day is no great boost to morale.

Fly fishing, it must be concluded, isn’t an activity for anyone with the following: high self-esteem, a friend who fishes, or a family history of depression—you’re much better off with sports like limbo skating or parasailing where failure is much more pardonable.

“Ah,” retort the cerebral trout bums. “It’s all about the journey, not the destination.” This, it seems to me, is the crux of the matter. One might as well say that fishing isn’t about fishing. But this brand of useless platitude smacks of something sinister. We’ve all begun to notice that the people who come up with these quips either leave the river full of sore-mouthed fish at day’s end or head home with a creel as empty as it was when they started. It would seem that the only people who have time to be meditative while fishing are clearly good enough that it’s of no consequence, or bad enough that they must concoct ointments for their troubled souls.

Most of the fish I‘ve caught, I’m convinced, pitied me. (This hunch is proven to my satisfaction every time I’ve got a decent rainbow within netting distance and he hits “eject.” Coincidentally, this recalls that ethical question of barbed vs. barbless hooks.) Be that as it may, can I with dignity and sincerity, throw out a bobbered line with a live grasshopper at its weighted end? The thought of actually catching something without the tears, the imprecations, the pomp and circumstance, sends shivers down the spine.

I hope to decry this unease, this shame-culture that, like a bony osprey circling a stringer of juicy browns, looms over the innocent bystander amidst the sanctimonious babble of the hip, new-agey fisher. I’m perfectly alright with the fellow's private practice, but like the regulations for the Emigrant to Pine Creek stretch, reason has its limits. When the moralistic angler salts with proverbs and aphorisms the tender wound of mediocrity, he fashions a rod for his own back. Soon, his tai chi casting tips will clear the stream of inferior intellects and he will find himself saluting the sun with no one to grab the net or camera. “In wilderness is the preservation of the world,” said Thoreau, but equally important to the work of preservation is the fish story. The great lies of the century must be saved for posterity. If we jettison this rich heritage of fibs for the “be-one-with-the-river,” “enjoy the ups and downs” jargon, what will we have left? We, the common fly fishers, must act before the false cast becomes the gold standard and stop lying to ourselves so that we may proudly lie to each other once again.