In the Flow

Studying CFS.

As temperatures rise and a season’s worth of snowfall melts and pours down the mountains, area rivers and streams turn from frozen trickles into raging rivers.

Sometime between the high water of spring and the low water of autumn, our rivers are perfect for floating and fishing. But when is the right time to get on the water, and how will you know? To understand the right time to float, we must first understand how river flows are measured and what those numbers actually mean.

River flows—commonly called “streamflows”—are measured in cubic feet per second, or CFS. Looking at any river gauge measurement will tell you the current CFS at that particular spot. Because the layman seldom measures water in cubic feet, CFS is commonly contextualized as basketballs flowing down the river: if the Gallatin is running at 1,000 CFS, imagine 1,000 basketballs of water flowing by a given spot on the river every second. Yeah, it’s pretty cool.

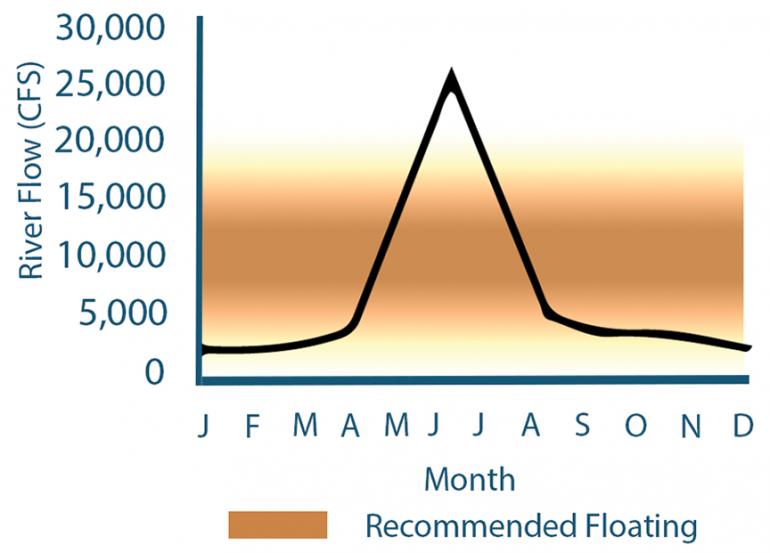

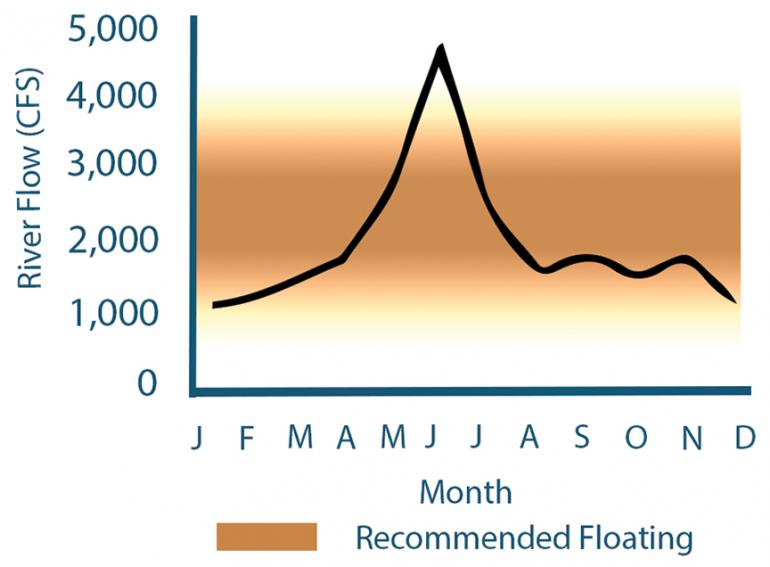

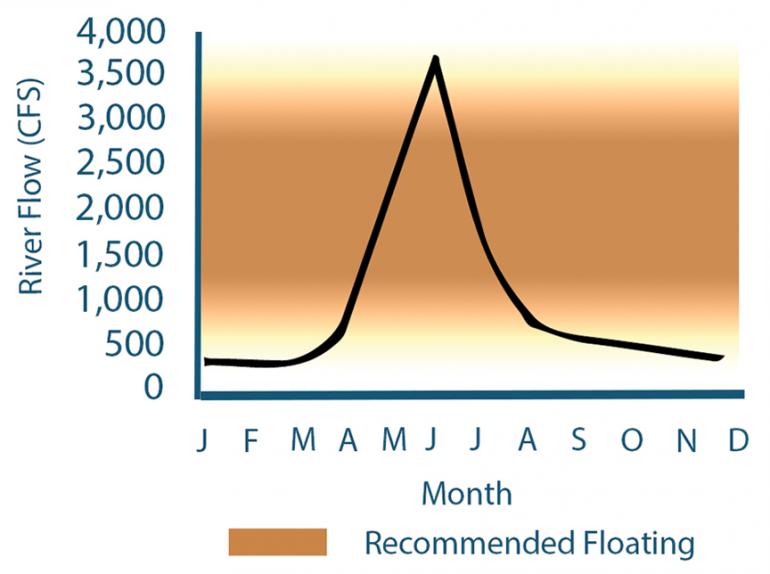

We also must understand that every river is different. The Yellowstone will generally carry more CFS than the Gallatin, because it is a larger, higher-volume river. It has a wider and deeper channel and substantially more water flowing into it from myriad upstream tributaries. This means that when the Yellowstone is running “low,” it may still have a CFS much higher than that of a low-volume river nearby—like the Gallatin. Conversely, during spring runoff, these low-volume rivers may have a relatively small CFS reading compared to larger rivers, but still be considered “high water.”

To know how streamflows translate for a given river, head to waterdata.usgs.gov to see current, median, and suggested flows for area rivers.

Strained Streamflows

Our world depends on natural cycles of change and transition. As seasons evolve from one year to the next, the climate of each period contributes to the natural conditions of its successor. For example, Bozeman’s 2010-2011 season saw a large amount of snowfall, resulting in high streamflows for the Gallatin River that summer.

Records of the Gallatin's streamflow near Gallatin Gateway date back as far as 1892, when the maximum discharge reached 8,060 cubic feet per second (CFS). Other high years include 1899, when the streamflow at Logan hit 9,840 CFS. These springs undoubtedly followed heavy winters with deep snowpacks and are marked as historical flood stages for the Gallatin River. Recordings from recent years show an average of about 6,000-7,000 CFS in early July, when streamflows are often at their peak.

Winter conditions are not solely responsible for streamflow levels in the spring and summer. Civilization has also played a role in shaping our waterways. Not only has the development of roofs, roads, and parking lots created excess runoff, but irrigation and groundwater pumping has also modified streamflow to an unnatural level.

The Western U.S. has a long history of excessive irrigation, so much that our ecosystems and culture relies on a high level of streamflow. With an increased need to conserve water, combined with the effects of climate change, hydrologists are worried that improvements in irrigation efficacy could reduce the streamflows we’ve come to depend on. As our environmental awareness continues to grow, we can only hope to maintain as natural a streamflow as possible, and not disrupt the river cycles any further.—Jersey Griggs