Freaks of Nature

The colorful leaves on Montana’s tree of life.

Montana and Yellowstone are graced with bountiful and familiar wildlife—the charismatic megafauna that are splashed across calendars and tourism brochures. We name things after them, we stalk them with camera and scope, we hunt them and mount their heads on our trophy castle walls.

But deep in the leaf litter, under the snowbanks, in the dark of night, high in the vast and busy sky, and lost in the endless grasslands, lurk lesser-known but no less fascinating critters and plants. Nature is endlessly creative and mysterious, and at times her creations are downright bizarre. These are some of Montana’s freaks of nature.

Rubber Boa (Charina bottae)

The rubber boa sounds like a child’s toy snake, but it is an actual constrictor found in the mountains of Montana. When you think boa constrictor, you don’t think Bridger Mountains. Yet that is where I have seen these strange little snakes—in Sypes Canyon among the limestone outcroppings.

Most northerly of all boas, rubber boas are cousins to rainforest species like boa constrictors. They are nonvenomous and only dangerous if you are a mouse or frog. Rubber boas spend a lot of time hiding from predators and digesting their occasional meals. They will seek out nests of rodents and eat the young while fending off the mother mouse with their tails, which can be scarred from these battles.

Smooth and dark gray, rubber boas are blunt and appear to have a head at each end. The longest they get is about 28 inches, so this is one small and skinny freak of nature. Rubber boas don’t bite people but can emit a potent musk. Next time you emit a potent aroma in the backcountry, blame it on a boa.

Barred Tiger Salamander, a.k.a. Axolotl (Ambystoma mavortium)

If you’re ever in Virginia City, take a side trip to the Axolotl Lakes. See if you can find an axolotl—a large aquatic salamander that inhabits some Montana water bodies. Then consider that true axolotls live only in two mountain lakes in Mexico, where they are known as water dogs. They are found in aquariums around the world where they are known to be able to regenerate missing body parts. But here in Montana we have North America’s largest salamander, the barred tiger salamander—a beautiful amphibian that may mimic its southern cousins by failing to grow up.

Most barred tiger salamanders are typical amphibians, undergoing metamorphosis, emerging from eggs in the water as aquatic tadpoles. Triggered by stressors such as predation or the drying up of seasonal wetland habitat, most salamanders lose their gills and become terrestrial, air-breathing adults. They then live on land until it is time to return to the water to lay eggs. In some cases, these salamanders resort to cannibalism to grow fast enough to leave their pothole pond before it dries up. The cannibalistic ones have large teeth and wider heads—the better to eat you with, my dear.

Axolotls, in contrast, keep their feathery external gills and wide, fish-like tails, and stick to their aquatic form. This “failure to launch” is known as neoteny. They can breed, though, assuring the species will go on. These unusual amphibians can live up to 15 years and reach a foot in length.

Neoteny among barred tiger salamanders appears to result from ideal habitat with plenty of water and no predators such as crayfish or trout. This leaves the salamanders in no rush to mature, and in some cases they completely abandon terrestrial living.

Although barred tiger salamanders are common, the axolotl version is rare, found only in two of the ten lakes at Axolotl Lakes and in a few ponds near West Yellowstone. Introduction of fish has wiped them out from some lakes. If you find one, leave it alone—there are not alotl them.

Swainson’s Hawk (Buteo swainsoni)

The elegant Swainson’s hawk normally feeds on the three Rs: rabbits, rodents, and reptiles. But when not breeding it switches to a diet of insects, favoring grasshoppers and dragonflies. With phenomenal soaring abilities, Swainson’s hawks migrate in large numbers to the grasslands of Argentina, making them one of our most well-traveled birds. They form vast “kettles” of thousands of birds, often mixing flocks with other migrators.

If you visit Yellowstone Lake in summer, look for Swainson’s hawks hovering over the Lake Yellowstone Hotel. They can soar so well, they appear to be barely moving as the wind streams in off the lake.

Brown-Headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater)

If you spend much time in Yellowstone around the bison, you will notice the large brown birds that perch on their backs in summer, hitching a comfortable ride. These are brown-headed cowbirds, the most common “brood parasite” in North America. These crafty blackbirds do not bother to make a nest or raise their own young, instead producing dozens of eggs that they lay in the nests of other birds. The young cowbirds are big and aggressive, and often out-compete the nestlings that belong there.

While cowbirds may lay their eggs in a wide variety of nests, most females specialize in parasitizing one species. Cowbird eggs hatch faster and the chicks grow more quickly than other birds, most of which do not recognize that they have intruders in the nest.

Uinta Ground Squirrel (Spermophilus armatus)

Are Unita ground squirrels? If they dig up your yard or pasture, probably not. Lucky for you they disappear for much of the year.

Nicknamed gophers, picket-pins, and whistle pigs, ground squirrels are some of the longest hibernators of any mammal. Here in Bozeman, we find mainly the Richardson’s ground squirrel (Spermophilus richardsonii), which are animals of the open prairie (and lawn), while in Yellowstone Park, the squeaking, scurrying masses are Uintas, which prefer sagebrush habitat.

During spring and summer, ground squirrels are everywhere, and can give people the creeps for their habit of eating their road-killed cousins. Their calls are entertaining, with six distinct sounds: chirps, squeals, squawks, trills, growls, and teeth chattering.

The young are fun to watch as they wrestle and chase one another. But they disappear in July or August, vanishing into their burrows for a long sleep until about mid-March. As the snow starts to melt they can be seen sitting at their dens looking groggy, wondering where the year went.

Ground squirrels compose important prey for just about everything that eats other animals—badgers, coyotes, foxes, hawks, owls, wolves, bears... anything but humans. People like to shoot them for sport, but eating them... not so much.

Northern Water Shrew (Sorex palustris) and American Pygmy Shrew (Sorex hoyl)

Montana hosts 11 species of shrew—tiny predators that are always hungry and must eat up to 90 percent of their bodyweight every day. The most unusual are the western water shrew and the pygmy shrew. Water shrews swim in ice-cold creeks and ponds, consuming small fish, insects, tadpoles, and even other shrews. Their eyesight is poor, so they use hearing and touch to locate their prey.

The American pygmy shrew is the smallest of all mammals on the continent, weighing the same as a dime. Yet it is still a ferocious animal and hunts nearly nonstop, consuming three times its own bodyweight in food each day in an intense fight against hunger.

Northern Bog Lemming (Synaptomys borealis)

When you think “lemming,” you might imagine fat arctic rodents rushing en masse off a cliff to their doom. Montana has its own lemming—the northern bog lemming. They are homebodies living—as you might suspect—in wet, boggy areas. They roam a range of up to one acre, but they don’t jump off cliffs together. Montana is the southern end of their range, and they tend to be isolated (unlike northern lemmings) due to their small ranges and limited wetland habitats. Bog lemmings need pristine wetlands, so Research Natural Areas set aside by the Forest Service can benefit these obscure and furry beasties.

Porcupine (Erithizon dorsatum)

Most people recognize the beaver as the world’s second-largest rodent (after the capybara of South America), but did you know the porcupine is the third-largest?

Sometimes known as needle beavers or revenge possums, porcupines are forest and shrubland dwellers with a serious arsenal. Up to 30,000 specially-adapted hairs cover their bodies in the forms of quills. When harassed, a porcupine will turn its back and fluff up its quills to present a serious defense. Anyone with a dog that has gotten into a porky knowns how nasty these quills are.

Despite this formidable defense, porcupines are in catastrophic decline in Montana’s mountains, and no one seems to know why. I used to find them in the Crazy Mountains, Bridger Canyon, and in the forests of the Continental Divide, but they are nearly impossible to find in the high country anymore. They do appear to still inhabit lower-elevation areas.

Porcupines are preyed upon by mountain lions and by fishers that have learned to flip them over and attack their vulnerable bellies. They are also indiscriminately shot due to their habit of eating bark off seedling trees and their threat to hunting dogs.

These huge rodents are awkward climbers, but still spend a lot of time in trees where they gnaw the bark off branches for food. On a hiking trip years ago, my friends and I chased one up a tree and I nearly paid with my hide for this harassment. The stressed porky fell from the tree and nearly landed on me.

Contrary to popular belief, porcupines cannot throw their quills, but they do have a large tail covered with quills that they can slap with. The quills are barbed, making them hard to remove. Porcupines do make some bizarre noises such as grunts, squeaks, and mumbles that sound like they are talking to themselves. Apparently they may den communally, though how these prickle pigs can do so is a mystery.

Roundleaf Sundew (Drosera rotundifolia)

Roundleaf sundew, also known as common sundew, is a plant that is not satisfied with mere photosynthesis. Found in bogs and wetlands that are often acidic and thus lack nutrients, the sundew has developed a taste for flesh.

Sticky, “dewy” drops of mucilage cover the hairy leaves of the plant. Attracted by the apparently abundant nectar, insects land on the sundew and become ensnared. There, they are slowly digested by the hungry plant. The ammonia that the sundew extracts from its victims replaces the nitrogen that most plants absorb from the soil.

Found around the northern parts of the world, sundew is quite common, and Montana hosts three species. These little bug-eaters are doing their part to control annoying insects, all while enjoying a hearty meaty meal.

Woodland Pinedrops (Pterospora andromedea)

As you wander the vast forests of western Montana, keep an eye out for pinedrops. Pale stems up to a foot tall draped with dangling pink or white upside-down flowers poke up from soil under evergreen trees. These ghostly members of Indian-pipe family are parasites, getting their nutrients from mycorrhizal fungi that link up with pine trees. Pinedrops have no leaves and do not photosynthesize, relying on their hosts to survive.

Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana)

Our fastest native land animal is the handsome and familiar pronghorn. These artiodactyl (even-toed, hoofed) mammals are the super-sprinters of the Great Plains, achieving speeds of 55mph which they can sustain for up to 800 yards, and up to 42mph for a full mile. Pronghorn can ditch any now extant predator (except a bullet or arrow), indicating that they evolved to outrun now-extinct predators like North American cheetahs. These uber-athletes have excellent vison and overdeveloped windpipes, hearts, and lungs.

The skull of the pronghorn has a permanent bony horn upon which a sheath of keratin grows, forming the handsome pronged black horn. The animals shed these sheaths every year. “Speedgoats” also have scent glands on their white rumps, which they flare when alarmed, releasing a buttery popcorn aroma.

Built for speed and needing to migrate, pronghorns are not good jumpers, so fences can be a major barrier for them unless they can squeeze underneath. In Greater Yellowstone, pronghorn migrate up to 200 miles between winter and summer range. They are intolerant of deep snow and may get stranded by large snowstorms like those in the winter of 2022-23.

Moose, Elk, and Deer (Cervidae spp.)

These magnificent herd animals, found around the northern world, grow antlers that shed each year and must regrow. Though these animals may seem normal compared to some of the freaks I describe, no other mammal has faster-growing tissue than a cervid growing antlers. The “velvet” or skin and hair covering the antler supplies the blood, but the calcium must come from their bodies and their diet. Elk antlers can grow an inch per day and moose, given good food and habitat, can put on a whole pound of antler per day.

Antlers are necessary to these beasts for display during breeding season, for fighting for the right to mate, as tools for scratching themselves, as weapons to ward off predators, and even for reaching leaves and branches to eat.

So next time you are horn hunting, or sitting down to a serving of Cervidae, consider what these critters demand of their bodies to produce those magnificent antlers.

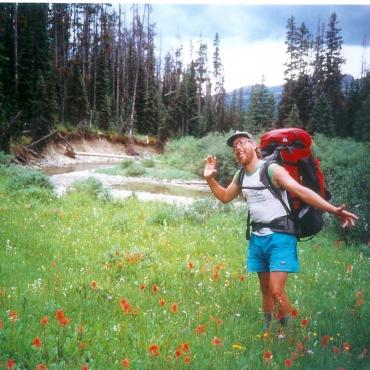

Human (Homo sapiens)

The so-called wise ape is a freak of nature for many reasons—not the least of which are our opposable thumbs and overdeveloped, overly-busy brains. But our athletic prowess is truly impressive when let loose.

A very fit human can outrun any animal over the long haul, including antelope, horses, wolves, and gazelles. Think about that when and if you run (or in my case watch) a marathon. We can run for so long partly due to our ability to shed excess heat via sweat glands (2-4 million of them) that cover our bodies, and because of the absence of fur on our bodies. Our two-legged running gait is another advantage, bouncing on extremely springy leg tendons that store elastic energy. We developed this Forrest Gump ability via “persistence hunting,” wherein our ancestors ran down prey until it was exhausted.

Be it an immature water dog, a ravenous mini-mammal, a carnivorous plant, or a tireless biped, Montana is home to some freaky life forms. Every living thing is strange and wondrous the closer you look, and here in Big Sky Country life is everywhere. Get out there and take a gander—you just might find something even weirder.

Phil Knight is a guide/naturalist who moved to Bozeman in 1985, fleeing a life of indolence and sloth back East. He’s traveled to seven continents and seen some crazy stuff.