Spilling the Beans

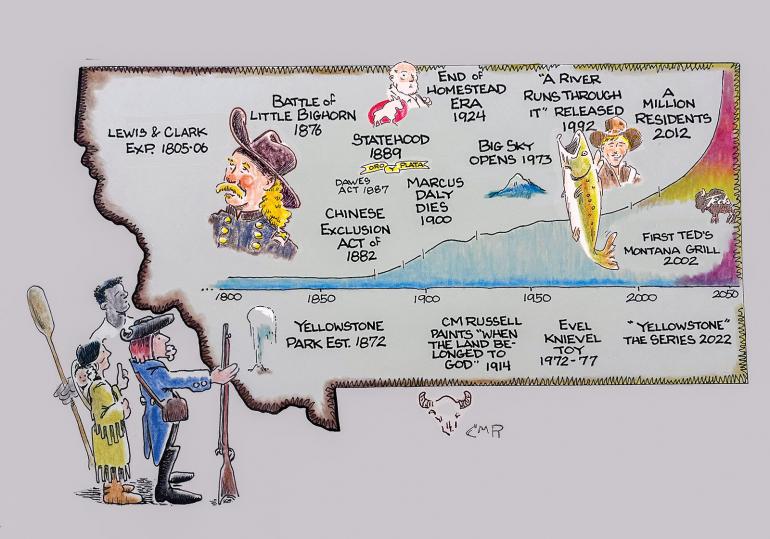

The eclectic cast of characters who put Montana on the map.

As the state of Montana settles into its newfound status of having more than a million year-round residents, it seems somehow proper to examine both the historic and contemporary record of what attracts otherwise sentient, right-minded adults to this godforsaken corner of the globe.

One could begin, I suppose, with the great geological forces that raised up and mineralized the northern Rockies. The twin attractions of stunning vistas and valuable natural resources forever welded romance to commerce in the Last Best Place to Treasure Big Sky Country’s Land of Shining Mountains.

Chamber of Commerce slogans aside, who were the people that came to shape our state’s burgeoning—if not fully diverse—demographics? I sometimes reflect dimly upon possible answers. An almost constant stream of newcomers has arrived to Montana over the past couple centuries, but so what? Well, I want to know who spilled the beans.

Others arrived during the gold-rush era as well: white Unionist northerners, black and brown folks looking for better opportunities, and notably, the Chinese who reworked placer mining spoils and built the Union Pacific railroad.

Certainly, captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark warrant special attention as influential early promoters of the region. As their expedition toiled up the Missouri, Lewis remembered his federal political benefactors and named today’s Jefferson, Madison, Gallatin, Dearborn, and Smith rivers. Nomenclature matters. Our mountain ranges and rivers are today front and center on real-estate and tourism advertisements, and embedded within popular television shows.

And while their western expedition is heralded as a great achievement, we’re quick to gloss over the darker sides. Co-captain Clark may have been the first to bring an enslaved black person into the far reaches of the newly-minted Upper Louisiana Territory in 1805. York, however, did not receive his promised freedom upon return to St. Louis. Sacajawea, the celebrated and well-remembered teenaged Shoshone interpreter, was by all modern definitions trafficked—by the Hidatsa tribe to her husband, the Canadian fur-trapper and expedition member Touissant Charbonneau. While York is mostly lost to history, Sacajawea lives on through numerous Montana place names, including a peak in the Bridger Mountains, a city park in Livingston, and a historic hotel in Three Forks. The captains were compelling journal writers, though, and detailed descriptions of the country and its wildlife are still widely quoted, perhaps most famous of all: “The men caught a nomber [sic] of fine… large Trout.”

More than half a century later, the Civil War dispersed many southerners to the Montana Territory and its riches, including the legendary “Four Georgians” who founded Helena’s Last Chance Gulch. Place names stand testimony, but scrubbing is well underway to remove the Confederate stain from our creeks and cities—including the 2017 removal of a Confederate monument in Helena, to name one.

Others arrived during the gold-rush era as well: white Unionist northerners, black and brown folks looking for better opportunities, and notably, the Chinese who reworked placer mining spoils and built the Union Pacific railroad. The Englishman Thomas J. Dimsdale filtered down from Canada to Virginia City and documented vigilante activities in the territory’s first newspaper, the Montana Post. Typical of the times, Dimsdale greatly exaggerated the riches of the mining district and rabble-roused against the thousands of Chinese arriving from California.

Vigilante forays extended into the late nineteenth century and helped set the stage for the territory’s vaunted tradition of secret societies, justice run amok, and bald-faced criminal behavior on the part of elected public officials and prominent members of the public. Inexplicably, “vigilante” remains a popular choice to name businesses in particular, but the word also sees service for at least one high-school mascot. Presumably, its sports teams don’t play by established rules.

Lt. Col. George Custer’s downfall at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876 built upon Montana Territory’s growing reputation as a place where just desserts could be as likely earned as meted out. The bravery of Custer’s famous Sioux opponents, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, and a year later the Nez Perce Chiefs Joseph and Looking Glass, surely inspired many to come and test their mettle in the territory. As is the case with the rest of the West, however, reservations were soon established and lines were drawn in the sand, clay, and rock, divvying up land ownership in the name of Manifest Destiny.

Vigilante forays extended into the late nineteenth century and helped set the stage for the territory’s vaunted tradition of secret societies, justice run amok, and bald-faced criminal behavior on the part of elected public officials and prominent members of the public.

Charlie Russell, the popular chronicler of the fading West, once advised a young artist to “hitch your wagon to romance,” and boy did he follow his own advice. His oil paintings in particular have proven emblematic of the beauty and freedom that Montana continues to imprint upon the bedazzled—young and old—as they set out to test and reinvent themselves in a fresh new land. But tucked away in his portfolio was also a bleaker picture of the west—one of starving cattle, emaciated and famished by the harsh Montana winter.

A curmudgeon to the end, Russell hated the exploitation of the plains, the end of the open range, and the humiliation of Native tribes. Perhaps ironically, Russell’s body of work touched off a hefty market for a cheesier brand of western artistic themes that today occupy acres of wall space in our hash houses, motel lobbies, and uptown galleries of “fine” western art.

Railroad giant James J. Hill attracted many thousands of people through his heavily advertised “fertile” plains during Montana’s homestead era. Understandably, the “honyockers” arrived by rail (the pejorative is derived from the German, “honey chaser”)—principally Hill’s Great Northern along the Hi-Line, and the Milwaukee Road through the belly of the state. By the mid-1920s, the parched prevailing winds blew these amateur farmers off their prairie quarter-sections like tumbleweeds before a thunderstorm. Montana’s population arc actually dipped during this period. The flinty souls that hunkered down and held out, though, would come to shape the socio-political landscape of that vast empty sector sometimes referred to casually as eastern Montana.

The Copper Kings and other figures of the Gilded Age were responsible for a great many people coming to Montana. Today we might call them “job creators.” The industrial sectors of Butte, Anaconda, Great Falls, Red Lodge, and later Lewistown attracted Irish, Italians, Scandinavians, Central and Eastern Europeans, and more looking to improve their lot in life. Could there have been a Dublin Gulch in Butte had it not been for Marcus Daly?

One of Turner's quislings busted me decades ago while I was making out with my girlfriend on a public road up Sixteen Mile Creek. From horseback the man said, “The sign says no stopping and standing.” That still smarts, although in truth we were probably practicing both.

Fabulous individual wealth was compiled at the top of the socio-economic structure, and Montana became a backdrop to show off the spoils of extractive commerce. Purchase of large tracts of land seemed a time-honored way; running for elected office a close second. These rich traditions remain, at least in the governor’s office, even as the source of wealth shifts from timber to info-tech, from minerals to media, cattle ranching to binomial coding.

Media mogul and restaurateur Ted Turner once refuted the charge that he was out to buy up every ranch in Gallatin County. That’s not true, he reportedly said. “I just want to buy up every ranch that borders mine.” Now one of the largest private landowners in the state, Turner has redeemed himself somewhat through impressive conservation and habitat efforts on his ranches. Still, one of his quislings busted me decades ago while I was making out with my girlfriend on a public road up Sixteen Mile Creek. From horseback the man said, “The sign says no stopping and standing.” That still smarts, although in truth we were probably practicing both.

Writers have certainly played a part in publicizing our state to a wider audience. As an occasional visitor, Hemingway’s influence is mostly tangential, although the main character in For Whom the Bell Tolls is from Red Lodge. Steinbeck famously wrote of his love of Montana in the book, Travels with Charley (you know the quote: “For other states I have admiration, respect, recognition, even some affection. But with Montana it is love.”) Travels was written in his dotage, though, and Steinbeck never portrayed Montana as a novel setting that I know of.

But Norman Maclean sure did, and his influential semi-autobiographic novella, A River Runs Though It, was interpreted on the silver screen in 1992 by California native Robert Redford. A movie based on the Jim Harrison novel Legends of the Fall came out a few years later, followed up by The Horse Whisperer in 1998. Hollywood’s got legs when it comes to activating the imagination. “I want to go to there,” the Gen X-ers, Millennials, and Gen Z-ers must have whispered to themselves as images of an idyllic Montana flickered seductively before their retinas.

Musicians? Oh, sure. Who can forget the John Denver earworm of “Rocky Mountain High,” which put immediate pressure on Montana as a way cooler place than the already-sullied Colorado? I suppose Jimmy Buffett gets a nod for setting songs here and dropping place names such as that memorable “Night in Montana.” Further, the release of “Livingston Saturday Night” and Thomas McGuane’s movie Rancho Deluxe in 1975 essentially timestamp the founding of “Glitter Gulch” in Paradise Valley.

Beginning with his retirement in the early 1970s, broadcaster Chet Huntley became a tireless promoter of his home state; and one can trace the development of Big Sky, Moonlight Basin, and the ultra-exclusive Montana real-estate and recreation clubs to his early vision. “If you build it, they will come.” And then build their own, evidently. One wonders whether his ashes are in a tornado over what has become of his beloved Gallatin Canyon.

Who are the influential personalities behind Montana’s population growth in more recent years, I wonder? Curious, I asked around and got some intriguing suggestions.

The late daredevil Evel Knievel—throughout his successes and smashing failures—never turned his back on the old hometown. I am flummoxed that the Evel Knievel Museum, which was founded in Butte, today lives on in Topeka, Kansas. Still, just count the Harley Davidsons out on the Montana highways come late summer.

The Freemen movement in east-central Montana in the mid-1990s comes to mind, as do the mountain men-cum-kidnappers Dan and Don Nichols, and the letter-bomber Ted Kaczynski. Can we not credit the media attention that befell these villainous individuals for attracting a certain brand of pilgrim to our state?

Who are the influential personalities behind Montana’s population growth in more recent years, I wonder? Curious, I asked around and got some intriguing suggestions.

Nominations among writers include the late novelist Ivan Doig, author of the artful This House of Sky. The artists Monte Dolack and Russell Chatham are sometimes brought up. The winter-sports filmmaker Warren Miller got at least one recommendation, as did the dinosaur-hunter, movie consultant, and student-mentor Jack Horner. The Butte-born and bred terrorist-killer Rob O’Neill brings some recent and very influential media attention, too.

It goes without saying that Taylor Sheridan, creator of the Texas-size Yellowstone television franchise, deserves a spot on the list. My own sister wears a “Don’t make me go Beth Dutton on you!” t-shirt when she visits.

While all nominees for selling Montana’s soul have earned a measure of respect and some a bushel of derision, none seem quite as influential as those previously mentioned Montana dream-weavers. Part of the beauty, I suppose, is the resulting fabric didn’t cost the Office of Tourism a single thin dime. Might be time, actually, to pump the brakes on both programs. “Ladies and gentlemen, our work here is complete.”

Some criticize Montana for its lack of cultural diversity, and indeed, that may seem to be the case. Whatever the depth and breadth of the Montana demographic profile, it can in part be blamed on the influence and actions of all these idealistic, adventurous, ambitious jaybirds. Their followers are out there, readers, I swear, in full pursuit of romance and commerce, putting names on places and things, and spilling the beans.

A million of ’em and more, and our numbers are only growing.