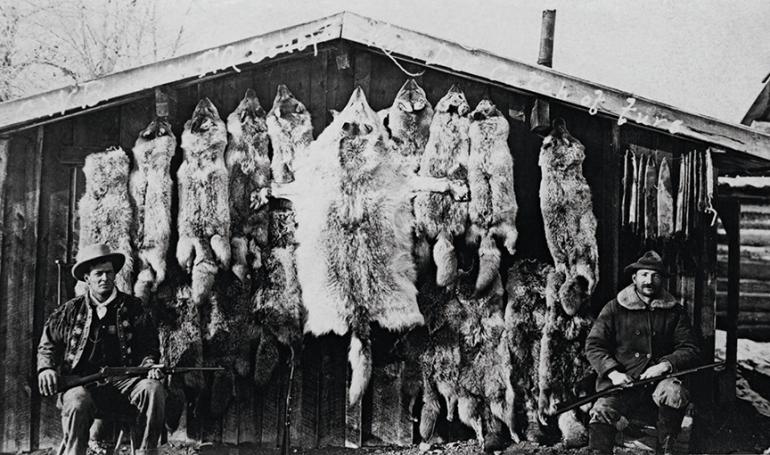

Killing Fields

A history of wolf-eradication in the Gallatin Valley.

As they traveled through present-day Montana, the men of the Lewis and Clark Expedition were struck by the great number of gray wolves in the area, often seen feasting on bison carcasses. They watched with some fascination a group of wolves bringing down a large elk. Today's biologists estimate the number of wolves in Montana at that time at around 200,000. By 1945, however, Canis lupus in Montana was almost extinct, although stories of "lone wolves" made the newspapers from time to time.

Before Europeans came to North America, the gray wolf roamed from coast to coast, as far south as central Mexico,and north throughout Canada. Immigrants to the New World brought with them from Europe a violent dislike and fear of the wolf, featured in so many folk tales. "Little Red Riding Hood" and "The Three Little Pigs" come to mind. The fables of Aesop characterized the wolf as wily, crafty, and evil.

The American wolf might live as long as fifteen years, but was more apt to expire at five or six years. The animal usually loped along at five miles an hour but, when hard pressed, could run at forty miles per hour. He usually hunted for food within a sixty-mile radius but could travel, if need be, a hundred miles in one day.

The fur trappers and traders of the 1830s and 1840s dismissed wolf fur as not worth the trouble when beaver pelts commanded a higher price. With the end of the beaver trade, the fur man turned to bison, deer, and wolf to skin and sell to eastern markets. In the 1850s, the market for wolf fur increased, and since wolves were plentiful in the Montana area, a new kind of hunter emerged: the wolfer. Montana's stockmen encouraged the killing of wolves and offered a bounty for each animal killed. State and local agencies also offered bounties for wolves. Thus, the wolfer could benefit in two ways: he could sell the skin and he could collect a bounty ranging from one dollar to three dollars. Gallatin County offered $2.50 for each dead wolf. If the wolfer worked hard during the winter season gathering prime pelts, he could bring in as much as $2,000 from bounties and fur sales.

In November, the wolfer would set traps in places known to be inhabited by wolves. Or he would corner a wolf with the help of greyhounds, whippets, or staghounds and shoot the animal outright. The wolfer fed his dogs just enough to keep them keen for the hunt. At the beginning of the wolfing season, all the wolfer needed was food, camping equipment, and a good supply of ammunition. In addition, the hunter might possess a small supply of the most efficient wolf killer of all: strychnine.

A carcass laced with a small amount of strychnine, a grainy substance that looked like table salt, could attract and kill several dozen wolves within a short period of time. Before the 1880s, a dead buffalo might hold the poison; after the American bison was gone from the plains, another dead animal would suffice, most probably a cow. Some wolfers sprinkled a carcass with strychnine in the deep of winter, returning in the spring to find dead wolves sprawled around the poisoned animal.

Wolfers tended to smell bad, and most people assumed that the strychnine was the cause of the odor. Skinning dead wolves, however, produced a pungent stench not easily removed from the wolfers’ clothing. It is probable, moreover, that the hunters did not bathe often during the winter months.

During the 1890s, a bounty of five dollars was offered for wolf pups. The wolfer then added a supply of dynamite to his winter outfit and became expert in blasting the dens of resident wolves, killing both the mother and the pups.

From 1870 to 1877, an estimated 55,000 wolves were killed in Montana. By 1911, the Montana wolf was becoming extinct except in the northern parts of the state. Homesteaders in remote areas of the Gallatin Valley, however, would still hear wolves howl at night in the 1920s. During that time, the U. S. Forest Service trapped a number of wolves in the Gallatin River drainage. By 1933, the state had dropped the bounty for a dead wolf.

Roberta Carkeek Cheney, in her Names on the Face of Montana, tells how the northeastern Montana town of Wolf Point got its name: "One winter a party of wolfers – who made up the lowest rung of the social ladder in frontier life – captured several hundred gray wolves in very cold weather. They hauled carcasses into camp and stacked the frozen wolves in huge piles, facing the river where the steamboats came in – the grisly mound of wolves gave the town its name."

Throughout the state, a number of "last wolf" stories appeared from time to time. These wolves were often imbued with amazing abilities to evade their hunters. The Gallatin County "last wolf" story, however, seemed more pathetic than heroic. On April 30, 1941, a 106-pound wolf measuring six feet, two inches from his nose to the tip of his tail was shot near Three Forks by Warren Leland and Al Johnson. The animal's fur was grizzled from old age and also carried metal and wire imbedded in its pelt from earlier bouts with traps. The men theorized that the wolf had traveled north from the wilderness high country near the sources of Cherry Creek.

Wolves have returned to parts of Montana, either on their own or by transplant. It is doubtful that the professional wolfer will return as well, although the violent dislike and fear of the wolf by some remains strong.