Lady Liberty

Hunting and freedom in the national forest.

The evening before bow season opened, I loaded up a bike-trailer with camping gear and pedaled into a heavily timbered drainage outside Bozeman. Arriving at a Douglas fir–cloaked hillside well past dark, I hastily made camp as irrational fears of lurking bears and intruders crept over me.

That night, as I lay in my sleeping bag, branches broke outside my tent. I grabbed my bear spray and tried to stay calm. Then I heard it—the chilling whistle of an elk bugle. Seconds later, more erupted deep down the canyon.

As I settled back to sleep, fear turned to contentment. I was finally living out my bow-hunting fantasy: a solitary camp, eavesdropping on animals, and anticipating a sneak into the woods before first light. I’d have preferred hunting deeper in the wilderness, but my bum knee and frenzied work schedule had bound me closer to the trailhead. So I sought a familiar drainage in the Custer-Gallatin National Forest, and hoped other archers would overlook its nearby game trails, buck rubs, and hidden meadows.

Despite the noisy bulls the first night, the following day was quiet, with little sign of elk or deer. On the second morning, a light mist filled the air and heavy clouds sunk low into the glacial-carved valley.

Enjoying the view, I almost overlooked the two bucks grazing the edge of a nearby meadow. I crouched behind a ponderosa pine and took off my boots and pack. When the deer turned away, I began my stalk.

Several hours later, they were still weaving through the forest ahead of me, picking over the last of summer’s forage. I’d snuck within range many times, but my shot was either obscured by brush or they were looking right at me, preventing me from drawing my bow.

The task seemed impossible. Ungulates, as prey animals, have to be alert—and this was my first as attempt at being a close-range predator. Small, seemingly insignificant details suddenly demanded my attention—shifts in the breeze, the rustle of my jacket, a quiet sniffle, or the snap of a twig. The hunt hinged on restraining my reflexes, and I had to wait for everything to line up perfectly.

Finally, both deer stopped moving, though my position wasn’t great. From behind a skinny fir sapling, I could see fragments of their ears and antlers. They seemed to be watching my tree, which wasn’t so much hiding me as much as breaking up my shape.

Just breathing felt precarious. After a short while, they bedded, unaware of my presence just 10 steps away. I no longer felt like an interloper, just another animal capable of melting into the forest. Had the stalk failed, I’d still have found what I came for—the heightened sense of awareness one experiences when stalking in the woods.

It’s these moments during hunts, and subtler ones, too, that I realize how valuable public land is. As a hunter, a national forest is much more than just a place for recreation. It’s an opportunity allowing us to transcend the separation between modern human and ancient nature, be it just for a morning.

Public land is the essence of freedom, an invitation to exercise a primal form of self-sufficiency, and, in the process, connect with an ecosystem. Hunting’s conservation legacy stems from the late 1800s, when sportsmen spoke out and stood down robber barons and their political allies. We see that same struggle today as hunters are forced to confront politicians hell-bent on privatizing federal lands. There is a gut-level connection to public land that all hunters share. And this energy gives me hope that the movement to privatize them will ultimately fail.

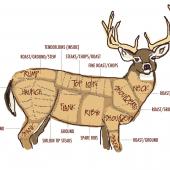

Eventually, the deer stood, breaking my trance, and continued grazing. Soon after that, I lost them as they hurried across a game trail. I followed, fearing they were long gone. When I reached a small meadow flanked by willows I caught sight of them again, and this time, I had a shot. Muscle memory took over as I drew my bow, aimed, and released the arrow. It hit behind the buck’s shoulder, and I watched anxiously for a few long seconds as he bounded into the conifers, then fell. As I anticipated his last breath, I felt the weight of a life leaving, then a rush of gratitude toward him, his habitat, and the land around me. This anonymous corner of national forest would feed my husband and me through the winter, making it just as spectacular and invaluable as any wilderness or national park. And just as worthy of protection.

This story originally appeared in High Country News.