Wordsmiths of SW MT: Doug Peacock

Sitting down with author Doug Peacock.

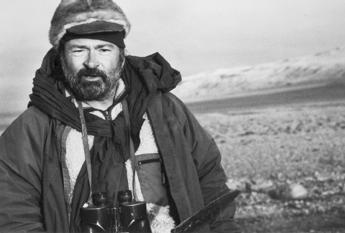

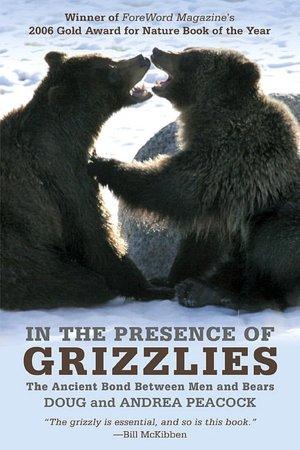

Doug Peacock’s home is not far from Bozeman, near his friend Jim Harrison’s. The two lay up fat for the winter (just like the bears before hibernation) over the neighborhood BBQ. But if you ask Doug where home really is, he’ll tell you it’s up and down the Rocky Mountains from Canada all the way to Mexico. He discovered them as a backpacking teenager who just wanted to be alone and crawled into the mountains “like a wounded animal” after Vietnam. There he discovered grizzlies, whom he says saved his life and became the subject of his first novel. He is a champion for the endangered bear, was one of Edward Abbey’s closest friends, and is the person who inspired Abbey’s Hayduke character in The Monkey Wrench Gang. His most recent books are Walking It Off and The Essential Grizzly (the latter was co-written with his wife Andrea).

What’s one of your favorite words?

There’s a word associated with grizzly bears that I’m fond of, it’s called hyperphagia. It means to eat excessively. It’s a metabolic state grizzlies go in late in the year when they have to lay on the fat for hibernation. When I’m cooking with Jim Harrison, he’s also very fond of the word. We end up in that state.

What profession other than writing would you like to participate in?

I can’t work for anybody. I’ve had this fundamental problem all my life and now my children are suffering from it as young adults. I can’t work for anybody else. I’ve been unemployable all my life—so scribbling and lecturing is about all I do. I also really enjoy talking to younger people.

What do you think is your best piece of work and your worst piece of work?

I wrote a little story about a painted cave in Baja that has never been published; I think that’s my best.

The worst experience is: I tried to do a news assignment for New Republic. There was a biosphere project where all these new-age yuppies were going to seal themselves in these things for three years or some bullshit like that. That was a nightmare. I did this on deadline. I wrote this thing in 24 or 48 hours and got it in. They called me and said, “Well, it wasn’t quite what we were looking for.” I got so pissed, I said, “Why didn’t you write it yourself… and don’t call back ever.”

Everyone’s heard the adage “write what you know,” but we all can’t be experts in all things. How do you personally go about researching a subject, and how do you know when you’ve got enough knowledge to write about it?

I tend to read everything I can get my hands on. I’m not a very good journalist. I’m like Ed Abbey, I wouldn’t let a bunch of unimportant facts get in the way of telling a good story. And I know that about myself.

I will read all the primary papers and if I get the guts up I will call up three or four essential field workers whose dates on things like glacial erratics are totally critical to the argument about when people came over here, where they came from and who was first and all that bullshit. I read everything authoritatively on the subject.

Coupled with that, I’ve got my own experience in the field. I’ve been hacking around the woods for six decades and I’m fairly comfortable with my skin. When I write my book, it’s not going to be an academic third-person book.

What is your daily writing regimen?

I’m a slob, I live a slothful life. I’m a pig and I’m ashamed of myself. What I do best is I get up in the morning and I go to work right away. At my fire lookout, I have a cup of coffee and start banging away at the keys. I didn’t set out to be a writer, I became a writer by default because I can’t make a living any other way. If I start rewriting, it dilutes a lot of power and language.

I found out—Jim Harrison advised me of this—there’s a certain speed that you are comfortable with, it’s kind of like walking. I do my best work when I’m really inspired and I write really fast. I think about the way sentences sound. If a sentence sounds good, I’ll write it down. And after I write it down, I don’t fuck with it much. The best writing, I hardly touch a word. It doesn’t happen often.

Were you a bookworm as a kid?

I read for self-preservation. I read everything. All the great American literature. I read Henry Miller who led me to existential literature—the French poets and the great Russians. If you looked under my bed right now, you can see Moby Dick, The Iliad, crap like that. I like Faulkner, War and Peace, The Odyssey.

What’s the worst thing that’s ever happened to you and how is it reflected in your writing?

I saw a lot of dead children in Vietnam, a whole lot of dead children. I was the senior Green Beret medic in the middle of no place. All the bodies came through me and there were a lot of little bodies. That resulted in my politic. Anything that results in a dead child, I’m against. I value life so much. All of life: wildlife, animal life, human life. That’s a very searing experience, not something that you get over but something that you try to build a constructive life knowing what exists in the world—and a lot of it is darkness.

Do you collect anything?

When I was young, I was interested in hunting arrowheads. I wasn’t interested in collecting them so much as going to the places and wondering about the people who lived there before. I’ve done that all my life. Archaeology is not really scientific, it’s really a curiosity about the land and how people lived on that land 10,000 years ago—sustainably with the land and I always think about that, any place I go. I have people drive me around and I look at the old riverbeds and I wonder what it was like 1,000 years ago and what animals lived there.

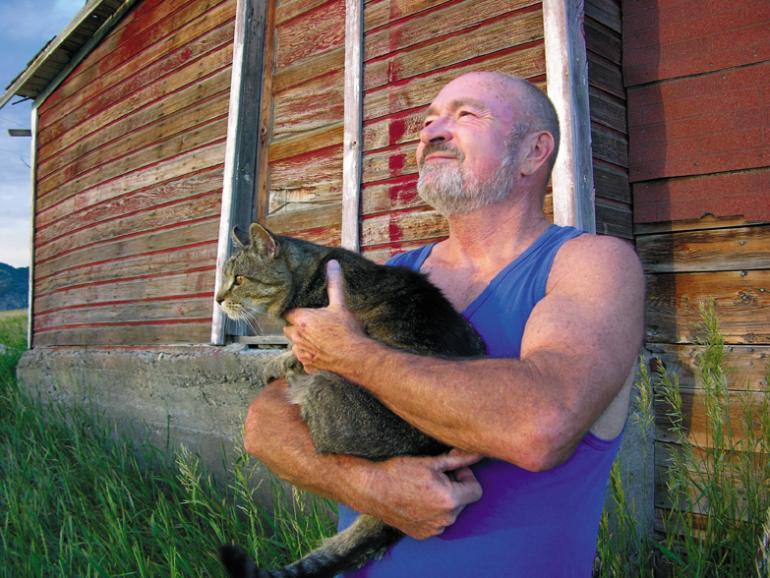

Are you a dog person or a cat person?

That’s kind of like asking what caused Paleo-extinction: over-hunting by early man or climate change? The fact is both of them did. One does not exclude the other. I’m both a dog and cat person. There’s four cats in this house right now.

In general, which do you prefer as a means of communication from the outside world: TV, newspapers, or the internet?

I listen to the radio.

How were you first introduced to the wilderness?

My dad was a boy-scouter, so even before I was old enough to be a scout, I got taken out to all these great places in the wildest part of Michigan and cut loose to run by myself. I spent a lot of time alone. I was left by myself to get lost and make mistakes and learn my way around.

I had a maternal grandfather who took me trout fishing. There was a great bird refuge, big, swampy wetlands. I spent all my spare time in a canoe looking at birds or hunting arrowheads or pheasants.

By the time I was a teenager I was taking long solo backpack trips by myself. And I discovered the Rocky Mountains as a teenager. Once I discovered the Rockies, I was home and it is still home. It was always home.

Tell us about your years after Vietnam.

Once I came back from Vietnam I was like a lot of other vets, I was out of sorts, I couldn’t be around people and I didn’t want to talk to anybody, so I went to the one place I’ve always been comfortable, and that’s the wilderness. I crawled back into it like a wounded animal and I camped out for about 15 years. I started out in the Wind Rivers. My memoir, Grizzly Years was about those years. I ended up in Yellowstone and there I ran into grizzly bears and they absolutely riveted my attention. At that time it was exactly what I needed. I needed to be where self-indulgence is utterly impossible. You are not the top dog out there. You hear better, you smell better, you don’t think about your stock portfolio or your girlfriend. It’s a very effortless way to enter the ancient flow of nature, to live like our species has always lived. For 99 percent of our time on earth our species have lived in what today are the remnants of that habitat. We were a hunting animal; we lived with animals who were also capable of hunting us. Grizzly bears became invaluable in my life.

When did you start writing?

I’ve always kept a notebook. I had a lot of close friends that were writers. I really needed a job, but I didn’t like to be tied down. I remember Ed Abbey telling me, “You can apply for a seasonal employment with the Forest Service; they give you a quitting date to look forward to.”

I was one of the worst backcountry rangers ever. Anarchists make really lousy law enforcement. I lived far enough in the backcountry that I couldn’t see anyone. I became a fire lookout in Glacier Park. I had a daughter and I had to make some money. I had my dad’s old typewriter at Huckleberry Lookout in Glacier Park and I started banging away, that’s where I wrote Grizzly Years.

The baby needed new shoes. I was making like $4,000 a year with a wife and daughter and soon to have a son.

How did you meet your wife?

I had a collie dog, Larry. It was my only close friend. She came in and befriended my dog.

BOOKS BY DOUG PEACOCK

The Essential Grizzly (2006) co-author Andrea Peacock

Walking It Off (2005)

Baja! (1991)

Grizzly Years (1990)