The Sky Buzzard: Summer Stars

No rip-snortin’, self-respectin’ Western movie would be without them. Our cowboy hero, his horse shot out from underneath him, one cartridge left in his six-gun and one swallow in his canteen, staggers across the burning desert landscape toward the next waterhole. And what circles above? That black, wide-winged opportunist, the buzzard—two, four, eight of them, soaring on invisible thermals, waiting for their next snack.

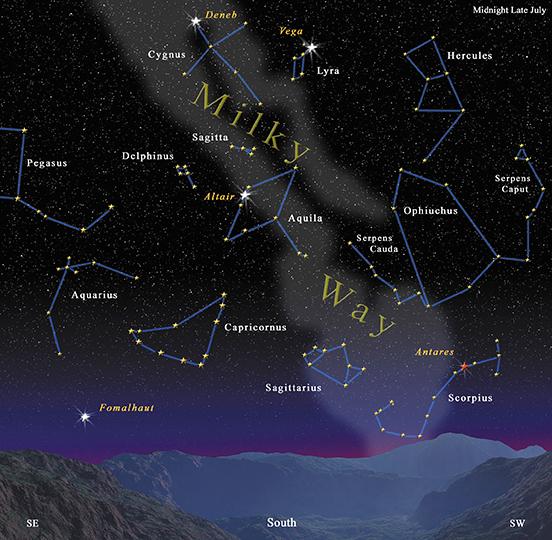

In the heat of our Western summers, the buzzard doesn’t stop circling at sunset, for the sharp-eyed and knowledgeable can find the bird soaring aloft even among the stars—in the guise of a musical instrument. It’s easy enough to find; look above you on the late evenings of summer, and its presence is betrayed by a bright, white star passing nearly overhead after midnight by July first, about 11:30 pm by August 1, and about 9:30 by the start of September. The star is Vega, the brightest of the trio of suns forming the sizeable Summer Triangle encompassing three separate constellations. Vega’s constellation is quite small, however, consisting primarily of itself and a parallelogram of fainter stars alongside. It’s Lyra, the lyre, or Greek harp—aka the vulture or buzzard in the sky.

The Arabs, who also knew something of burning desert landscapes, placed such a bird here. But the Greeks chose to picture a lyre, and a very famous one to boot. It was, in fact, the very first lyre, crafted by the clever god Hermes (Mercury) from a tortoise shell he found lying on the banks of the Nile in ages past. He traded it to Apollo for the caduceus, the staff that became Hermes’ signature accessory, and Apollo gave the lyre to one Orpheus, who coaxed such beautiful music out of it that his playing was said to charm the very rocks and trees.

The lyre also charmed Orpheus’ wife, Eurydice, but not for long. She had an unfortunate encounter with a poisonous snake one day, which sent her packing to the Underworld to the chagrin of Orpheus. In a daring move, the harpist played his way into the Underworld himself, and so charmed Hades, the presiding god, that Hades agreed to release Eurydice back to the World Above so long as Orpheus never looked back for her on the way out. Still strumming his lyre, Orpheus retraced his steps, but just before reaching safety, couldn’t resist looking back to see if his wife was following. She was, but in the instant he spied her, she disappeared, and Orpheus emerged from his adventure with nothing but his lyre.

He wandered the world sadly after that, catching a gig here and there, charming the pants off all who listened, and—as an eligible widower—attracted the advances of a number of single women. He rebuffed them all, however, and angered enough of them so that they ganged up and began pelting him with slings and arrows. All the missles were likewise charmed by the music of the lyre, however, and fell harmlessly to the ground—until the noise of the women drowned out the music, and a couple of the darts found their mark, sending Orpheus at last to join his wife.

The lyre fell into a river, and Zeus, the king of the gods, sent down a vulture to snatch it out of the stream and carry it into the sky. And there they remain today. Bright Vega is embedded in the frame of the instrument, and the adjacent starry parallelogram marks the strings. Imagine the vulture behind, with Vega also marking its beak, and the tableau is complete—and come full circle back to the buzzard in the sky.

Vega itself is a star of some repute—the first discovered to be encircled by leftover dust from its formation, vindicating the theory that planetary systems form from residual debris of starbirth. The theory has since been further bolstered by the detection of planetary companions for a number of nearby stars, and there is recent evidence that Vega itself may have parlayed some of its surrounding debris into a couple of large planets.

Its rank as fifth-brightest star in the sky attracts attention in any case, as it did for the Chinese and Japanese who saw in Vega the Weaver Princess, separated from her beloved Cowherd (the star Altair) by the river of the Milky Way. On one night a year, say the Japanese—the seventh day of the seventh month—magpies form a bridge so the lovers can be reunited.

Magpies, vultures—the night sky teems with western birds. Let them remind you to keep that canteen full, as you watch the stars circle aloft on sparkling Western nights.