Lasso in the Sky

Ah, spring—when a young cowboy’s fancy turns to thoughts of, well, calf roping and branding and the sorts of things that make boy calves sing soprano in the herd. And as if to remind the cowpuncher of his springtime lariat work, the sky sports a starry lasso of its own.

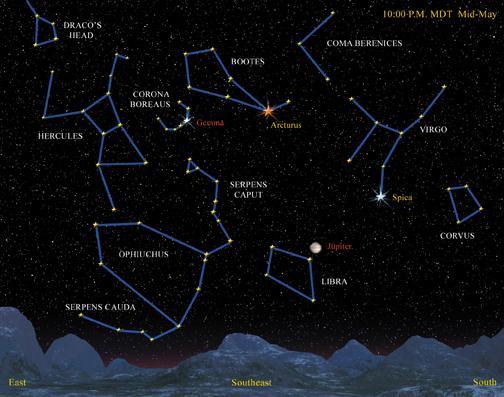

Use the high-flying Big Dipper, which pivots just north of overhead in the mid-evenings of May, as a starting point. Follow the curve of the Dipper’s handle to trace an arc to Arcturus—the pale orange star anchoring the bottom of the kite shape of Bootes, the herdsman. Look just left of the upper part of the kite and you’ll find the circlet of stars that makes Corona Borealis, the Northern Crown—also known as the “lasso in the sky.” Its brightest star, known alternately as Gemma or Alphecca, is a white sun bigger and brighter than our own and is located about 75 light-years away.

To call Corona a lasso, though, is to reveal your tenderfootedness, for real cowboys would more likely refer to this piece of equipment as a “catch loop” or simply a “loop.” Other cultures called it many other things: the Arabs saw a beggar’s bowl in these stars; the Chinese, a string of coins—or alternatively, a prison where one might go if one purloined the coin strings of others. The Mikmak Indians called the pattern the Bear’s Den, the Pawnee saw a Circle of Chiefs, and the Blackfeet found the outlined body of Spider God sitting in the sky, the nearby stars of Hercules marking the center of his web.

The constellation’s pretensions as royal headgear derive from a Greek tale. It seems that Dionysus (the Roman Bacchus), god of wine, was touring the beaches of the Greek isle of Naxos when he came upon one Ariadne, a princess who was feeling sorry for herself after having been abandoned there by the cad Theseus after she helped him dispatch the Minotaur on the island of Crete. Taking a serious shine to the princess, Dionysus impulsively professed his love. Ariadne, wanting to make sure it wasn’t just the wine talking, told him to prove it. Dionysus promptly did so by snatching off his crown and tossing it into the heavens to proclaim his devotion for all to see. Princess Ariadne, duly impressed, agreed to marry the god, and his crown still hangs to this day in the heavens, an eternal stamp on the couple’s prenuptial agreement.

The Shawnee people use the star pattern to tell another love story—this one about the young chief Algon and his love interest from the other side of the cosmos. The Star Maid, as she was called, was the youngest of twelve daughters of the Sky Chief. The sisters had a habit of descending to Earth at night in a great basket to do a circle dance in a forest clearing. Algon spied the Star Maid there one night, fell for her hard, and snared her for his own while her sisters fled back into the sky. He took her home to become his wife, love bloomed between them, and they had a son called the Star Boy.

But soon this mixed marriage had problems, because the Star Maid was growing unhappy with her separation from the Sky World. So Algon moved his family to his wife’s former upscale neighborhood. Then Algon grew sad, for he missed his home on Earth. The clever chief solved the dilemma by turning himself and his family into white hawks. And now it’s said that if you see such a bird in the sky, it’s either Algon, the Star Maid, or the Star Boy commuting between heaven and Earth.

But the Star Maid’s sisters are still dancing, forming the circle of stars we call the Northern Crown. If you look closely, you can see that the circle is not complete; the sisters leave a place for the Star Maid, hoping she will one day return and dance with them again in the sky. Have a look for yourself on the next clear night, and see if she’s come back. And if, on the cool nights of spring, you feel an urge to rope something, be it gawky calf or significant other, chalk it up to the influence of the starry lasso in the sky!

Jim Manning is the head of the Office of Public Outreach Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, but maintains roots just "Outside Bozeman."

Night Skies

The Southwest Montana Astronomical Society (SMAS) invites those interested to their club meeting on March 31 in the Museum of the Rockies’ Red Star classroom at 7:30pm. Meetings are scheduled for the last Friday of each month.

The SMAS has not yet finalized details for its Astronomy Day program at the Museum of the Rockies on May 6. Contact president Fred Birk at [email protected] for more info.

Taylor Planetarium at the Museum of the Rockies has several shows scheduled this spring:

Laser Dave Matthews - Until May 7

The music of the Dave Matthews Band combined with lighting effects and laser imagery.

How to Build a Planet - Until May 26

Watch the development of Earth in a program funded by the Montana Space Grant Consortium.

Native American Skies - Ongoing

A stellar tour from a Native American perspective, accompanied by tribal stories.

For times and other information, contact the planetarium at 994-2251 or visit www.montana.edu/wwwmor/.